“Ready to work?,” said Jesus “Chuy” Medrano jokingly to his 39 new hires following an exhaustive 13-hour trip from the Mexican border to Colorado. His men haven’t even had a chance to use the bathroom or even eat breakfast at this point, but their spirits are high. After all, landscaping season has just started, and Medrano’s men are ready to make some much deserved, and U.S. regulated money.

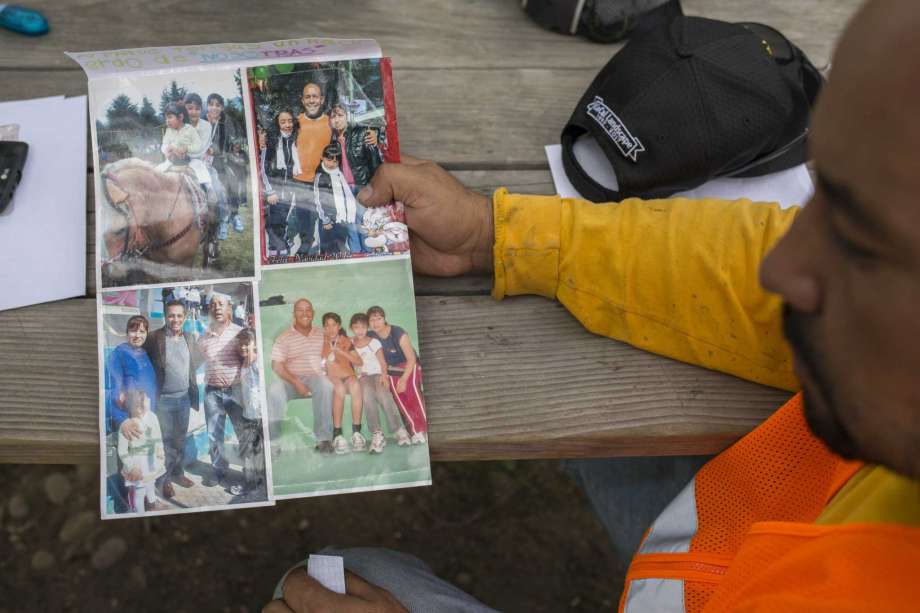

Mr. Medrano is the owner and founder of CoCal Landscape, a commercial landscaping service in Denver that started back in 1992. With 25 years in the market, Medrano has built an enviable customer portfolio, which is why during the high season, the 63-year-old cowboy hat-wearing grandfather is always searching for committed employees that can preserve the company’s longstanding prestige.

This is why Medrano had to spend three days in the Ciudad Juarez U.S. Consulate to procure the highly expensive H-2B temporary work visas for this group of loyal Mexican migrants who don’t mind the invigorating, backbreaking work of an industrial landscaper.

But why did Medrano have to spend $32,000 in securing these visas? The answer is simple: no American (at least in his proximity) is willing to work under the life-affirming Colorado sun for the $14 an hour that Medrano’s company can pay beginners.

It’s not like Medrano hasn’t tried to hire American labor, it makes more sense for him to do so because it would save him trouble and money to just receive recruits in his office rather than having to travel to another country to find them. He even put up one of those expensive digital billboards on the highway that flashed “We’re hiring!” to little avail. “We hope they’re breathing and they have a pulse, and we hire them,” said Medrano to Chron.

CoCal even raised the hourly wage for unskilled laborers to $13.95 which stands at 50% percent more than the state’s minimum wage and grew lenient of workers absenteeism to the point where a foreman was pardoned after going AWOL on a two-week drinking binge. The company started hiring more women and was comprehensive of mothers tumultuous schedules, as well, but he would always end up short-staffed anyway.

Why? As Medrano tells it, many people would stand up and leave during orientation, claiming “I’m not going to do that for $14 an hour,” and those who did stay, unaccustomed to physical work, would start complaining about sore feet and blisters due to wearing work boots. At the end of the day, most would walk away after only three days, with only 73 people remaining out of the 222 new hires since February.

Unfortunately, Medrano needs to find another solution soon, because hiring foreign work might no longer be the commodity he could always turn to. With Donald Trump pressuring Congress to limit the number of H-2B visas from 85,000 to 60,000, this could very well be one of the last seasons Medrano will be able to recruit his trusted friends from south of the border.

This year he got lucky when the administration unexpectedly released an extra 15,000 visas in July. Medrano pounced at the opportunity to secure them in order to salvage the season, but again, a business can not rely on luck alone. What will be of Medrano’s enterprise when hiring foreign workers is no longer a choice? What will be of America if people are not willing to learn the meaning of hard work? What is the point in protecting jobs that no American wants? This lesson, and other, will be ones that Medrano is going to learn the hard way down the road.